Here is a story from my first year in India along with a few facts about life in the foothills of the Himalayan Mountains.

On our first trip to India, my former partner and I planned a weekend trip to meet his sister and her husband in Shimla. She wanted to visit because it was used as a setting in so many Bollywood movies. Early one morning we began our journey on a treacherous mountain road, racing 225 km across northern India in a rinky-dink cab with a madcap driver--even by Indian standards. He careened and jammed, reducing the almost seven hour trip from McLeod Ganj to under five. It was only my second long trip by car in India. This is not a myth: the roads and the driving are unlike anything in the West. Over 350 people a day die on Indian roads, which in a population of more than a billion plus seems miniscule until you figure into the calculation that fewer than 10% of the population use cars. It takes some getting used to.

The power brokers of the British Raj selected this idyllic spot for its summer headquarters when the heat of the plains became too much for their thin blood. A mile and half above sea level, Shimla is now the capital of Himachal Pradesh. It’s a more picture perfect hill station than our humble McLeod Ganj. There’s a pedestrian mall that you get up to via a crowded elevator, a substantial Anglican Church, a handsome stock of colonial buildings still in use as offices for the renowned Indian bureaucracy, lots of restaurants and coffee shops. A few of the fine bungalows that the highly placed British civil officers demanded for their families and staff have been carefully preserved.

One of the oldest small gauge railroads in India shuttled the overlords, their families and extensive retinue up the steep mountain. Though still connected to the Indian Railway, it’s kept in service as a tourist attraction. You pay your fare, ride a couple of stops, get off, cross the track, and wait for an uphill train. We’re not talking about Six Flags. We’re stepping back at least 150 years into the remnants of the British Raj.

For Hindus, Shimla is also revered as one of the traditional holy sites of Lord Hanuman. Though this goes back to ancient times, a very recent addition to the landscape has been a huge statue of the monkey god, 108 feet, higher up on Jakhu Hill (an anomaly in a land of the metric system, but probably something to do with the cost of concrete and getting to a mystic number. It’s very tall).

Early in the afternoon our little group took the toy train down hill. On the way back up we were told about a small temple that might be worth a visit. We either walked or grabbed a quick cab from the train station to a very typical Indian temple. Inside the gate one of the baba’s was chanting, breaking coconuts and pouring their milk over the bonnet of a devotee’s car; I noticed that it was not brand new; perhaps the new owner was trying to wipe the karmic slate clean in anticipation of treacherous mountain roads. The only way I can describe it is “very Indian.” Even though I’d met several Indian teachers in California, including Swami Muktananda who came with all the cultural guru trappings, I felt slightly uncomfortable. It was certainly not something that Father Halloran would be doing in the parking lot of Saint Catherine’s--breaking coconuts and pouring the milk over the hood of mother's Ford station wagon, but I can hardly get that image out of my head now that it's planted.

We managed to squeeze past this elaborate ritual and came into a large hall where there was some intense chanting, surprisingly so. In most Indian temples people line up, offer a few rupee notes, get a blessing and leave. As a Hanuman shrine, it was overrun with hundreds of monkeys scarfing up tons of bananas set out as offerings. Monkeys are particularly nasty creatures, and living in a temple courtyard does not make them civilized, but Saturday outing at a temple, and people were posing for selfies with the monkeys using their smartphones. The depth of the devotions was refreshing, but the whole scene still felt very foreign. There was a lot of family talk in Hindi and after a few pictures for the folks back home, I wandered off.

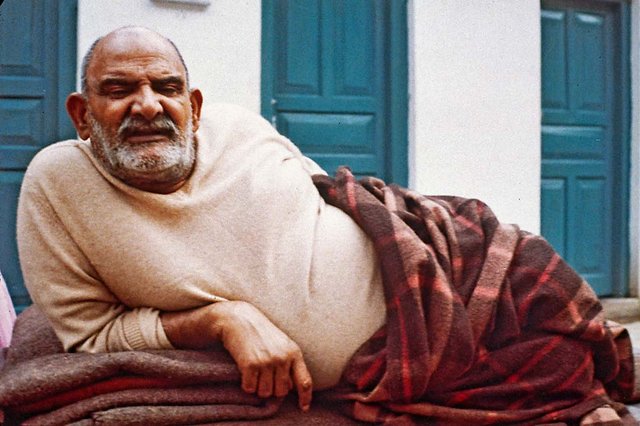

The temple was built into the side of a hill. I descended to the level below the main hall where there was another highly decorated temple on a small courtyard. I was the only person there. I wandered in, and was greeted by a life-sized statue of a baba, sādhu, or monk, lots of fresh flowers and food offerings. I’d stumbled into the samadhi shrine of the temple’s founder. I bowed, turned, and was about to leave when it hit me, really hit me! It was not that particular emotional feeling that Indians describe as bhakti. It was more deep recognition; “I know that man.” The lifelike, life sized, very colorful, idealized figure was definitely a person that I’d seen somewhere. I pulled out my phone and within a few minutes had solved the mystery. It was Neem Karoli Baba, Ram Dass’s guru. Neem Karoli was not from the plains of India. He’d spent his life wandering these hills of northern India. His main temple and ashram were further north in Uttarakhand but perhaps we’d found a subtemple, or the temple of one of his disciples. The deity fit; his protector, not quite sure how to describe the relationship, was Lord Hanuman.

The pieces tumbled together. You’ve probably heard about Ram Das. Who hasn’t? He wrote the wildly popular New Age book called “Be Here Now” in the 70’s. It became one of the Bibles of the hippies. I met him on four or five occasions. He was always extremely gracious and lively. Even in a large group, he seemed to be able to focus on you in a way that felt very personal. During my tenure as Director of Maitri, I asked him to come to Hartford Street to do a fundraiser. I remember that it was after Issan had died and Steve had resigned because Phil did the introduction.

Even though the enormous death HIV/AIDS toll had begun to decline by the mid-90’s, there were still thousands of infected men facing an early death. An overflowing crowd sat zazen in our small zendo. Ram Das sat in the teacher’s seat and, as I remember clearly, his head seemed to be on a swivel, bouncing around, while all the zennies were stiff as boards, staring straight ahead.

He began his talk with a kind chuckle and said, “I am going to talk about the Self and dying. Oh sorry, no-self, I have to remember that I am in a Buddhist crowd even if the notion entirely escapes me.” Then he began to talk about one of his visions after he first returned from India: to create a center for conscious dying. The idea was to establish a kind of ashram for people who were dying and interested in various conscious exercises, including mediation, during their dying process. He even said that he had a location picked out. Then he said that he, or the group that was working with him abandoned the idea because no one was interested. I wondered why he would throw this out into a group of gay men, the majority of whom were facing death. Was it a kind of challenge? How would they choose to spend their few precious last months, weeks, days?

Then he turned towards me and asked me about the hospice. I said that Issan had been committed to making life as normal as possible for the residents, but we had no requirement that residents had to be particularly conscious, spiritually or otherwise, during their last bit of this-life-alive time; that we were committed to allowing the individual's path to unfold. There were however a few residents who meditated as much as possible. He nodded and smiled.

We collected a few hundred dollars that evening to help pay the bills, but we received a different kind of gift, not pouring coconut milk over a second hard car, but an invitation to examine what was really important about life, especially when the end is definitely in sight.