Published Sunday, April 28, 2024

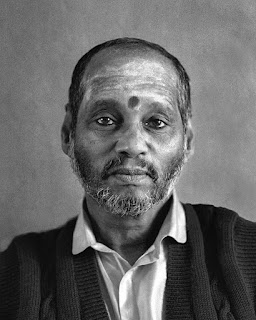

Muktananda

What I remember most about the evening was the fancy BMV with the vanity plates GURU 1, driven by a uniformed chauffeur. Muktananda and Werner Erhard were in the back seat. Baba’s translator, Swami Yogananda Jain, sat in front with the driver. The venue was the Masonic Auditorium atop Nob Hill. It had the impeccably smooth and professional rollout of an est event, but it was not, at least in my opinion, the important presentation of Siddhi Yoga it pretended to be. I would have to dig deep for anything that piqued my curiosity. I had listened to far too many sermons about grace, shanti, or shakti. What I saw was the Westernization of an Indian sadhu, sanitized but still containing a few tastefully presented cultural artifacts that might be interesting to spiritual seekers of New Age California. We might have been dusted with a peacock feather as we left, but I was definitely not impressed.

This was the second of Muktananda’s world tours. A few Westerners had become disciples. They’d purchased and begun refurbishing a large hall with a kitchen and some staff quarters in Emeryville. It was either ‘74 or ‘75 because I had taken my exclaustration and was living on the Oakland-Berkeley border with my fellow SAT member Hal Slate. It was also close to the end of the first SAT groups, but all the group members were still in active communication. One day, either Hal or I got a call that someone had arranged a private Darshan with Muktananda to be held late that afternoon before the public event at the ashram.

There were no more than 20 people in the room. I recognized Helen Palmer. As soon as Baba Muktananda entered and took his seat, he gestured towards Helen who got up, bowed, and went into the adjoining meditation room. She later told me that she was there because Muktananda was the best “hit” in town. Following a few remarks by Jain, Muktananda gestured towards me, and Jain asked me to come forward. I’d tried to find an appropriate gift. We were told that he liked hats. I had an old white Panama Hat from college that I’d trimmed with an orange ribbon and the end of a peacock feather. I’d wrapped it in plain white paper. I had already decided to skip the whole foot-kissing ritual. I sat before him in a kneeling position, said hello, and handed him my gift. After Jain or another assistant unwrapped it, he laughed uproariously, took off his hat, and put on the Panama. Then he handed me his orange skull cap and said in English, “Hat for a hat!” Then Jain translated a few questions about who I was, what I did, and something about a prince that I missed entirely, but others in the group were impressed. I returned to my seat.

Then Muktananda pointed to someone behind me and asked who he was. The young man said he was from Franklin Jones's (Da Free John) group and had come to extend their greetings to Baba. The conversation was suddenly doused with cold water. The drift of the questions I could follow went something like, well, I do hope he’s well, but where is he? He’s swamped, but he sends this box of cheap crummy chocolate balls from the ashram’s kitchen as a token of his respect. I had tried to be respectful within what I felt were my limits. Da Free John’s people didn’t swear or make foul gestures but seemed deliberately confrontational. Someone on the staff would be asked how the group made it onto the list of guests.

An hour in, I had a sense of heightened awareness, so when Jain invited questions from other guests, I was unprepared to respond to one woman’s question. She said she was epileptic. Was there anything she could do to prevent seizures? Muktananda became oddly professional and said he’d been a doctor before becoming a sadhu. He recommended drinking cow urine, preferably still warm, fresh from the cow. Now that I’ve lived in India and have some experience of village Ayurveda medicine, I realize that cow piss is a bit like aspirin. It is applied widely with little discrimination. But at that moment, I was facing total culture shock. Here I was in a guru’s ashram wearing his orange skull cap, getting carried away with lots of high energy, watching him dress down a fallen-away follower’s disciples, and listening to medical advice about the benefits of cow piss.

At that point, Jain said that we had to wrap things up. The time had come for the chanting, talk, and Darshan in the public hall. Afterward, please stay for dinner. I’m sure Hal and I stayed. Chanting the Guru Gita was very long. The poem praises the eternal guru, and his followers identified Muktananda as that guru. Singing praises of the divine guru in the presence of a human guru was a bit over the top for me, but I was also doing my best to dispel my preconceived ideas and prejudices.

The next day, I had a meeting at the Jesuit School. After meditation, I walked down Telegraph Avenue towards the campus. There was a bank just past Ashby, and I stopped to get 20 bucks from the ATM. I made my way back to the sidewalk, turned left, and stopped on the corner of Russell, waiting for the light. Before the signal turned green, my entire world was transformed. The experience is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to describe. It lit up. I’d been plugged in. First were colors I had never imagined. If I said I was floating in a whirlwind of electric particles, that wouldn’t do it justice. I knew exactly where I was and what I was doing, but the world was buzzing. It was somewhat akin to the few drug experiences I had had but far more vibrant, and I was present, not just an observer. It was wildly expansive, but the center held. I cannot say how long it lasted. It disappeared just as quickly as it had arrived. Part of me was stunned, but it was not the kind of experience that required me to put on my analytical hat and ponder it for a month. It just was. When I noticed that the light had changed to green, I had no idea how long I’d been standing there. I looked at my watch and realized that I would be late for lunch at the Jesuit School if I lingered. The universe returned to what it had been a few minutes, seconds, or nanoseconds before, and I continued walking north, though I remember being extremely careful of crossing traffic.

Later that afternoon, I realized I had received shaktipat, which yogis describe as the awakening of the dormant divine energy. I also realized why very little is written about these experiences other than that they happen. It was a wild experience. Maybe I could blame it on the orange skull cap.

I would have been a fool not to follow up on my experience to see if it led anywhere. I returned to the Oakland ashram but did not become a regular by any stretch of the imagination. I didn’t much like the Hindu trappings. I should be more precise: I didn’t particularly dislike them either, but I wasn't falling in love. The singing started to feel like uninspired Catholic guitar masses of the 70s. I felt that the people around Muktananda were there to feel some kind of spiritual high or bliss, but it was extremely self-centered. I had conversations with several Western sadhus again but was not inspired. I could not shake off their guru worship.

The staff announced a retreat, a long period of meditation at a center in the Santa Cruz Mountains. It was to last a week, which I could not manage. Still, I wanted to experience a longer concentrated meditation period, so I asked Muktananda personally at Darshan if I could attend only on the weekend. He quickly assented. I arrived late Friday afternoon after the long rush hour drive from San Francisco. I signed in and was directed to the shared cabin I’d been assigned. I set off into the woods. On the path, I passed Muktananda with his perpetual entourage of VIPs; Naranjo was among them. They were headed up to the main meditation pavilion. I bowed towards them. Muktananda nodded back. I continued to struggle along the densely overgrown path toward my bunk when suddenly I heard a deafening cracking sound. It sounded like a giant with enormous hands snapping his fingers right over my head or close to my ear. Then again. I found my cabin, threw down my sleeping bag, and made my way to the meditation hall. I wouldn’t return to bed for 36 hours.

An elaborate Krishna shrine had been set up in the middle of the room. Men would circumambulate for an hour, and then the women would take up the dance. It was not like the ecstatic airport Hari Krishna chanters, but that was the song, and it was not quiet. There were as I recall live musicians as well as spontaneous twirling and jumping. The chanting was modulated with slow and faster sections. When I did circumambulate, I was extremely restrained but didn’t feel out of place or forced into a fake religious fervor. We sat in what zen monks would consider a very loose meditation posture, men on one side of the room and women on the other. A guy in front of me was bouncing off the floor with what I was told were some kind of kriyas or loosening of the kundalini energy. Once, Muktananda came into the room and led the procession of men circling the Krisha shrine, but most of the time, he sat on the side in an elevated chair. There must have been a few breaks when Muktananda talked or answered questions. I remember the guy in front of me thanking Muktananda for his experience. Food was available during certain periods, but I don’t recall formal meal breaks. The dancing and singing went on day and night. It didn’t stop. The drive back to San Francisco was about 4 hours on a hazardous highway, so I made sure that I had a few hours of sleep before leaving, but other than that, I was in the meditation hall.

Once was enough. Despite these intense meditation experiences, I began to feel more and more disconnected from Muktananda. I continued to visit the Oakland ashram occasionally when he was there, which was less frequent. He had engagements in New York and southern California. There were now a huge number of people gathering around him. It had a cultish feel. There was also an extraordinary amount of money flowing into the organization.

One time, we were told through the SAT grapevine that Hoffman would visit. Knowing that Hoffman only went to make a public display of himself as Muktananda’s equal or to find some way to denigrate Muktananda, I was not going to miss it. After Hoffman’s private meeting, I wasn’t present, so I don’t know about the encounter, I was standing at the edge of the dining hall with others when Hoffman reappeared. Suddenly, he disappeared, and then, after a few minutes, he came into the room sheepishly carrying a plate of food or a bowl of soup, complaining loudly about Muktananda’s guards. “I know he’s very lonely. So I wanted to share soup with him and keep him company, but they wouldn’t let me in.”

I will now try to describe an experience that I have never written about or even talked about other than on one or two occasions and then privately. I think I’ve been afraid of either being called a madman or a failed sannyasin, neither of which is personally appealing. I can’t say with certainty what did happen other than it happened. I might have been deluded or hallucinating or carried away by an induced fervor, or perhaps it did occur, as I am going to describe. But I can't avoid telling the story if I demand complete honesty from Muktananda.

I forget the circumstances of my invitation. I was not a regular member of Naranjo’s inner circle, but either late afternoon or early evening, I went to Kathy and Claudio’s house in North Berkeley above the Arlington circle. When I arrived, there were only a few people. I only specifically remember my friend Danny Ross being there. Cheryl Dembe, who later became Sundari, might have also been present, as well as Luc Brebion. Other than that, I would have to pick and choose from a list of the usual suspects. I would have remembered if there’d been a very close friend with whom I might have shared and even asked questions about what seemed to happen.

One of the first things I clearly remember was a Scientology E Meter casually set up on the breakfast table. Until then, I had only heard rumors of Nanranjo’s experimentation with Auditing. However, seeing the device, which is nothing more than a galvanic skin response lie detector, the rumor was no more.

There was undoubtedly the usual friendly chit-chat. As it was beginning to get dark, Speeth and several others arrived. They came in through the front door. She was carrying a plain square cardboard box, slightly smaller than a bank box. In it were copies of a thin book, talks by Muktananda* that she and Donovan Bess had edited and published. She said that they were hot off the press, and the reason she was late was that she’d been at the airport saying goodbye to Muktananda before he and his entourage flew back to India, and she had wanted to share the new publication with him before he left. She gave us each a copy. We were sitting on the floor near the breakfast nook and some casual seating. I still had a clear view of the front door. The group was politely enthusiastic about Speeth and Bess’s work, thumbing through, reading bits and pieces here and there, smiling, laughing.

Then I looked up and noticed a very bright light that seemed to be coming through the front door. It was a long, oval shape and fit the door frame. It increased in intensity, the edges becoming brighter while the inside seemed reddish or orange. Suddenly, the actual shape of Muktananda’s body became clear. It was dressed as we had always seen him in darshan, but the clothing was diaphanous and brightly lit. His distinct facial features were also clearly visible. He was walking at a very deliberate pace, though the legs may not have been moving at all. He had the appearance and movement of a real human body, although it did not seem solid. I could still make out the door and the walls through him. It was eerily lifelike.

I do not know if I was the only person who saw this. There was no discussion, no questions, no expressions of shock and awe. The only thing that did happen was that someone in the group began to sing Om Namah Shivaya very softly. The figure started at the edge of the circle opposite me. It stood behind each person. I cannot remember if they were gestures, but the person became quiet. The figure moved clockwise until I could sense it standing behind me. That was the last thing I recall until we began to gather our things together to return home.

I am surprised that after an extraordinary experience, and I presume that others had some experience, we just returned to our everyday lives. I have hesitated to speak about it openly for almost 50 years. Many possible reactions exist to an apparent, even violent breaking of ordinary perception. One is silence. Nearly all modern writers talking about their drug experiences have expressed frustration. Most writings by the mystics are rarely self-explanatory. When you can’t say anything, nothing may be the best option. I have not used any language designed for extraordinary mystical experiences. Muktananda was not projecting an astral body. I am not calling it an apparition. I wonder if close disciples of devotees simply have these encounters and accept them as the “new normal,” but what I experienced was not ordinary by any stretch of the imagination.

What I can say honestly is that a revered Indian guru who was on a scheduled international flight from San Francisco to Mumbai appeared in an ordinary Berkeley house in the early evening. He was a real person or appeared incredibly life-like, although his body was diaphanous and bright. He was alive, not dead or resurrected, as in the Jesus narrative, but afterward, I could see Thomas’s meeting Jesus differently. And if the story of Thomas putting his hands in Jesus’s open wounds actually happened, I could also understand that the conversations recorded in the 20th Chapter of John took a few years to emerge.

Baba-ji is a lecher

The number of followers around Muktananda became overwhelming. Darshan was a circus. I can’t recall one talk I thought was memorable. No one seemed interested in psychological investigation. I stopped going. Siddha Yoga is a practice of energy transfer and a connection between the guru and his or her student. That wasn’t happening.

It was also clear that in a larger group, there were those who were close devotees or considered themselves close and those aspiring or even jealous. There was also an enormous amount of money now available. This is ripe terrain for abuse, distrust, and even warfare. It never reached the outrageous heights of Rajneeshpuram in Oregon, but cults are cults. The disintegration in trust was the beginning of the leaking of salacious details about Muktananda’s sex life.

Hoffman had been wrong, or perhaps very right. Muktananda did not lack company, and he may have been very lonely. I will not delve into his motivations, but soon, there were credible rumors that the guards who had blocked Hoffman from the private apartments invited many younger women, some even allegedly underage, to join Muktananda. He was not a celibate sadhu.

I’ve read many accounts from insiders, malcontents, and disenchanted followers. At some point, Muktananda gave up the celibate life, but he couldn’t just trade satguru for the role of a conventional married man. Krishna Murti’s long involvement with an older married woman might be a good example of a relationship I can understand and even sympathize with. What I think I can say with some understanding of the cultural divide between traditional Indian culture and Westernized ones, especially New Age California: Muktananda could not prey on younger Indian women--the taboos are too strong--but with many younger American women with liberated attitudes available, the doors opened. Most reports said the doors opened frequently, and it was not about nurturing human relationships. It was sex.

People try to defend him. I will only point to one of Muktananda’s most ardent supporters, Claudio Naranjo’s explanation: “I think Muktananda’s case is very complex. My own interpretation of him is that he was playing the role of a saint according to Western ideals or to cultural ideals in general. I think he was a saint in the real sense, which has nothing to do with that. For instance, it's the popular idea that a saint has no sexual life, and he was playing the role of a Brahmacharya, which I think was part of his cultural mission to be an educator on a large scale. It was fitting that he did that role, and my own evaluation of him is that he was clean because he was not a lecher.”

Claudio, let me be clear--your analysis is wrong. He was a lecher. His behavior was unethical and exploitative. If he were a Catholic priest, he would have been defrocked, or even in jail. He does not get a pass for trying to play the role of a Brahmacharya in some huge cultural shift.

Baba-Ji, you lied to us. You were not who you claimed to be. You were a lecher.

I’m unsure where I can begin to separate the man from the yogic powers or even if I have to. But I know where to place my allegiance and when to withdraw it.

Honesty is such a lonely word

Everyone is so untrue

Honesty is hardly ever heard

And mostly what I need from you

--Billy Joel

*The publication date of “Swami Muktananda,” edited by Kathleen Speeth & Donovan Bess is 1974, so my mental calculation is slightly off.